Digitally Reconstructing the Theatre Royal

By Freya Clare Smith (2016)

A warm thank you goes to Theatre Royal specialist, Conor Doyle, for providing access to some wonderful sources; to Nora Thornton (National Photographic Archive, National Library of Ireland) who assisted in finding historical photographs, which provided invaluable evidence for the theatre’s interior décor; and to Zoë Reid (Head of Conservation, National Archives of Ireland) for the wonderful conservation work completed on the original architectural plans.[1]

The research work that is now briefly introduced here represents the first ever undertaking in tackling the challenge of sourcing, collating, piecing together and synthesising many different types of historical evidence to begin digitally reconstructing and visualising this immense, complex and intriguing building, which still lives so vividly in the minds of a large section of the Irish population.

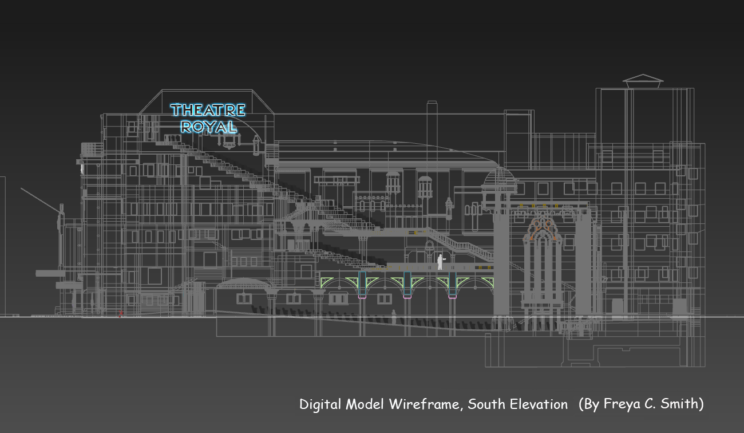

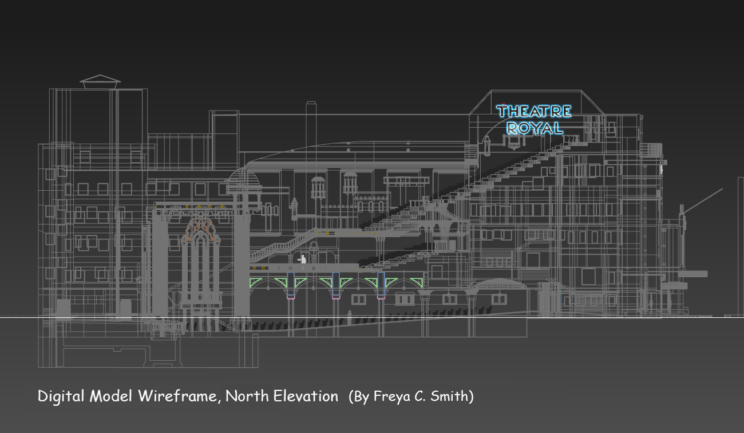

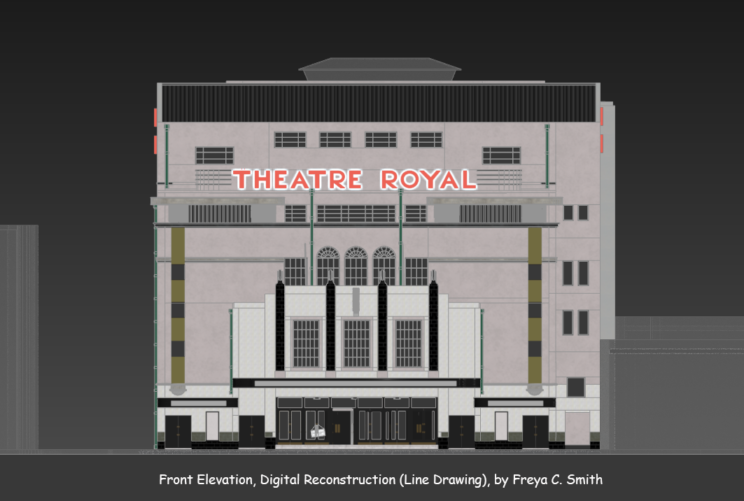

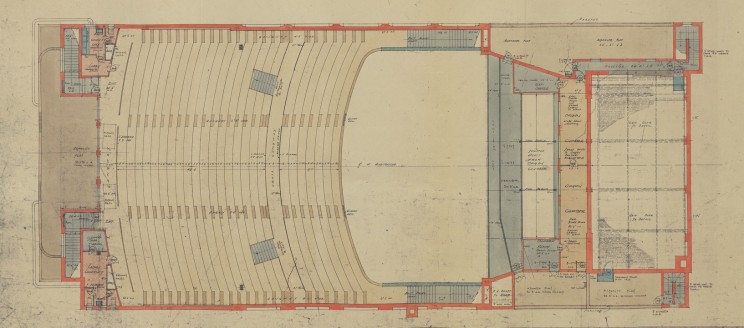

Rising above the surrounding city skyline, the Theatre Royal’s height reached an impressive 80 feet (25m) above ground level at either end, rose to approximately 65 feet (20m) across its middle section and had a footprint extending over an area of approximately 24,500 square feet.[2] It had room to entertain twice the audience size of the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre. Identifiable in the images above and below as a line of tiny theatre seats, the auditorium floor level gradually sloped downwards below ground level [3] adding to the vastness inside. There were also further technical and social spaces located beneath this level, such as the ‘subterranean’ bar located near the stage area. The theatre building included a complex warren of rooms at its front (or western) end. The overall design of this area, home to a variety of bars and tearooms, had socialising at its forefront. Also located in this area were retiring and dressing spaces, as well as offices and technical rooms, including a fully equipped film previewing room. At the very top of this front area, was a private social space, which (attested to by the emerging digital reconstruction) would have had a beautiful view across the Dublin skyline. This space was seemingly only accessible from a lift located in the front entrance foyer on the ground floor; and there are whispers about the ‘delights’/’plights’ awaiting one after being invited into this lift, which will hopefully be captured in the Oral History component of the project.

The auditorium stretched approximately 130 feet (40m) beyond this front area and rose to the full height of the building, containing two balcony areas. The stage was an impressive 40 feet (12.5m) in width and located to either side of it, rising to the full height of the building, were areas containing dressing rooms, and additional retiring spaces, offices and technical rooms, as well as an entrance-way into the adjoining Regal Cinema. Of particular note was the lavish interior décor throughout the building’s social spaces and performance areas, which is evidenced to have drawn inspiration from a number of different styles – both the stage area and the auditorium contained many decorative architectural features and elements that drew inspiration from the Alhambra for form/shape and that were also highly ornamented with complex Moorish-style inspired artistry and patterns from this historic site; whilst in contrast to this some of the social spaces at the front of house appear to have drawn on the Art Deco style.

The Moorish-style auditorium.

(Photograph: Unknown date, © The National Library of Ireland, G.A. Duncan.)

The size of the theatre, and the number of different spaces and architectural/decorative elements to model within the theatre, has presented many challenges in terms of the sheer quantity of geometry to represent; the number of different textures required; the size of these textures (both in terms of the area they must cover and their resolution); and in lighting the different spaces. Factors such as these have a significant impact on image and animation rendering times within digital modelling software and on performance (or the achievable frame rate) when developing within the real-time environment; as well as a significant impact on the time required to research, record, build and fine-tune such a reconstruction. A further consideration when building such a model is gaps or ‘blind spots’ in the evidence. Due to the immensity and highly decorative character of the third Theatre Royal, as well as the significant amount of research required to uncover suitable sources that can be used to model all areas of this complex structure, concentration in this phase is focused on digitally visualising the overall layout of the building, locating and mapping entrances and exits and commencing to detail the Art Deco facade and highly ornamented auditorium and stage areas; both a static digital model (3ds Max) and real-time digital model (Unity) are being simultaneously developed.

Sources: Evidence for modelling

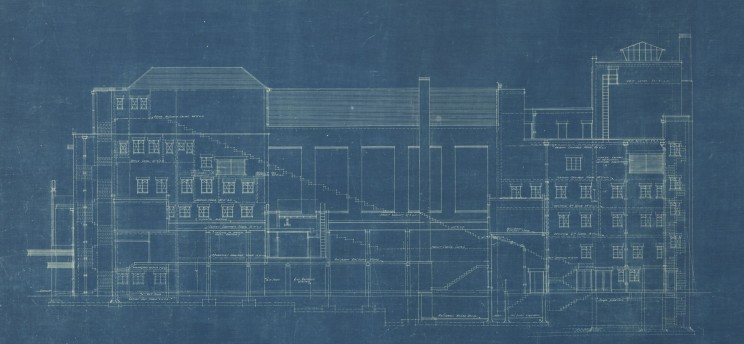

Coming now to the surviving sources and evidence, which could be used to begin digitally visualising this theatre: fortuitously the Abbey Theatre has been prolifically written about, has a dedicated archive and other primary sources have been thoughtfully donated to and carefully preserved by archives, such as the Irish Architectural Archive and the National Library of Ireland; sadly however, in the case of the 1935 Theatre Royal, secondary sources are more limited, there is unfortunately no dedicated archive, as the theatre did not continue on as did the Abbey, and thus finding sources with relevant details to build a reconstruction is like striking gold. A tiny hint, however, in the National Archives index indicated some potential. What was found far exceeded all expectation: a veritable treasure trove of uncatalogued original architectural blueprints and coloured diazotype prints of the third Theatre Royal dating to 1934 and 1935. Included in this collection are beautifully draughted plans for the various levels of this vast theatre, as well as elevations, longitudinal sections and cross sections (some of which are shown below).

Theatre Royal, South Elevation (blueprint); Date: March 1934

(Photograph: © The National Archives of Ireland)

Theatre Royal, Fourth Floor Plan (Diazotype / Hand Coloured); Date: March 1934

(Photograph: © The National Archives of Ireland)

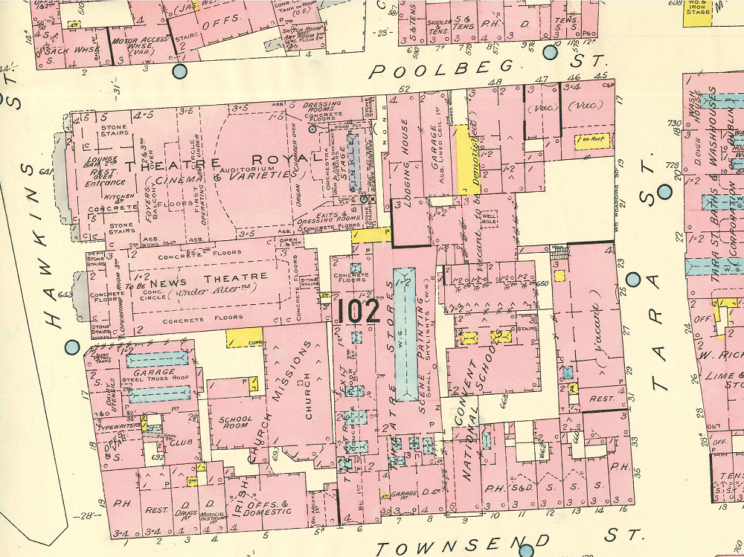

This was a fantastic find, which together with actual surviving physical remains, historical photographs, video footage of the theatre’s demolition, textual documents and other types of sources, such as a copy of the opening night souvenir brochure, has provided invaluable original evidence to begin digitally visualising this theatre. The initial step in this process involved a preliminary analysis of these prints, together with other sources that could provide dimensional evidence, such as and Ordnance Survey maps and Goad’s Fire Insurance plans (one of which, dating to 1938, is shown below) prior to deciding which evidence to bring into the 3D modelling environment.

Goad’s 1938 Fire Insurance Plan, Sheet 18

(Image: © Trinity College Dublin, Map Library)

In the case of the architectural prints the preliminary analysis identified that whilst there was a significant overlap in the information that both sets of prints provided they also provided a significant amount of complimentary additional evidence and could be used to cross-check dimensions. It was therefore decided to use both sets to model accurate and robust exterior and interior structural elements, as well as architectural design features, such as a beautiful domed ceiling located at the rear of the auditorium at stalls level. Following the careful conservation of these prints, by National Archive’s Conservator, Zoë Reid, and their digital capture, by National Archive’s Photographer, Eamonn Mulally, high resolution reproductions were brought into the 3D modellling environment. High resolution reproductions of Goad’s Fire Insurance plans and Ordnance Survey mapping were also brought into this environment to provide both comparative dimensional evidence and additional supporting evidence, particularly with locating and positioning the theatre relevant to the surrounding street, pavement and building context. Within this environment all architectural prints and supporting mapping evidence were scaled into real-world measurements. This provided the ideal set-up for creating both an accurate and to-scale digital model from the evidence.

Whilst it was clear from the preliminary analysis of these prints that they presented invaluable evidence for creating an accurately dimensioned visualisation of exterior and interior structural elements and architectural design features of the theatre, it was also clear that neither the blueprints nor the diazotype prints represented a complete picture of every aspect; that there were ‘blind spots’ or gaps in the evidence. Additionally, it is highly probable that neither set of prints represented or consisted of the drawings/prints that were actually used on-site by the contractors to build the structure. These prints were more than likely both revised immediately prior to construction and during construction, as the need arose to on-site specific adjustments during building-works. However, from a comparison with other evidence, such as historical photographs, it is highly probable that the drawings/prints used on-site during construction did not differ significantly overall. In this scenario, however, whilst the resultant exterior and interior structural elements of the theatre have been accurately ‘reconstructed’ from these available surviving sources, it must be clearly emphasized that the resultant digital model does not represent an ‘as built’ reconstruction and remains open to adjustments and amendments subject to the discovery of further evidence.

The current research work in this phase of the ‘reconstruction’ or visualisation process, nearing completion now, involves commencing to detail the Art Deco facade, and the auditorium and stage area and incorporating representations of some of the wonderful Moorish-style architectural features and decoration, inspired by the Alhambra in Spain. While no detailed drawings of these elements have yet been uncovered, they are shown in a range of other source types, in particular historical photographs, such as the iconic photograph of the Theatre Royal’s auditorium shown above, and more detailed photographs, dating to 1935, from a collection in the National Photograph Archive (National Library of Ireland), which will be uploaded once reproduction permissions have been agreed, as well as in artwork and video footage. The next phase, which comprises an oral history component that will hopefully reveal further details about the theatre’s architecture, décor and colour scheme, taking into consideration the technical challenges the Theatre Royal presents in terms of size and complexity outlined above, will review the evidence collated to date and look at digitally refining geometric details and visuals, including materials and fabrics.

Some Preliminary Screen Captures of the Digital Model in Progress

NOTE: The screen captures of the interior are currently presented in black and white: since the Theatre Royal presides within living memory, the digital model is to be taken forward in a series of Oral History interviews with former audience members, performers and staff and the thinking behind presenting it in this way, prior to these interviews, is that a black and white version will leave it open to more accurate memories being stimulated and recalled when the digital model or images of the digital model are viewed, particularly in terms of the colour scheme used.

![]() Supported by the European Union’s 7th Framework Programme

Supported by the European Union’s 7th Framework Programme